“Now they say they’re here to uphold the law / But they trample on our rights.”

Streets of Minneapolis – Bruce Springsteen

In recent months, an increasingly explicit attack has taken shape against grassroots social, cultural, and political experiences. The evictions and threats targeting long-standing spaces such as Leoncavallo and Askatasuna, as well as the pressures and intimidations directed at places like Spin Time, Officina 99, Labàs, and many others, cannot be read as isolated episodes or simple public-order issues. They are converging signals of a political line that sees the autonomous production of social life as problematic, if not openly incompatible with the current model of governance.

In Italy, social centres have never been merely “alternative” spaces. For over thirty years, they have functioned as laboratories of political and cultural experimentation, mutual aid, social cooperation, and artistic and musical production. They have often anticipated responses to real needs – housing, cultural, social – precisely at moments when public institutions were retreating, withdrawing, or delegating these functions to the market. It is this ability to hold together everyday life, culture, and conflict that makes them so difficult to govern today.

Striking these spaces means striking forms of collective organisation that produce meaning, relationships, and practices outside traditional institutional frameworks. In this sense, repression is not only an act of force but a strategy of normalisation: reducing the space of action for what exceeds, does not fit, and cannot be domesticated.

Security, control, selection

Alongside this direct attack, a broader and more pervasive phase has developed, one that can be defined without ambiguity as punitive. A phase that does not affect social centres alone, but the entire ecosystem of social life: cultural associations, live music venues, clubs, third-sector organisations, and experiences of social cooperation.

After the tragedy of Crans-Montana, the issue of “security” has become the crowbar used to introduce increasingly stringent controls on permits, labour regulations, and administrative and criminal responsibilities. A clampdown presented as technical, neutral, inevitable. Yet in practice, it operates through a very clear form of selection.

Large entertainment actors, equipped with capital, infrastructures, legal offices, and permanent consultancy networks, are not challenged. Instead, it is the realities based on proximity, precarious cultural labour, volunteering, and fragile economies that are crushed. In other words, everything that produces everyday social life in local territories is targeted.

In this context, security ceases to be a form of protection and becomes a device of governance. It does not openly prohibit; it makes things unworkable. It does not shut everyone down; it pushes out those who cannot sustain the bureaucratic and economic burden. It is a form of control that does not act only on illegality, but on what is considered excessive, non-conforming, politically inconvenient.

Mega-events, market logic vs living communities

This process becomes even clearer when viewed against the expansion of mega-events. While independent spaces and cultural associations are subjected to increasingly tight controls, large entertainment and live music formats continue to grow unhindered: ever more expensive tickets, ever larger audiences, sponsors and private funding playing an ever more central role.

This growth rarely strengthens local territories or cultural scenes. On the contrary, it functions as an extractive model: it arrives, consumes attention and resources, and leaves. Mega-events occupy symbolic space, social time, and often public resources, without building continuity or durable cultural infrastructures.

In recent years, even some of Europe’s major festivals have begun to show the cracks in this system. The case of Sónar in 2025 exposed the financialisation mechanisms governing many large events: opaque ownership structures, investment funds, governance arrangements increasingly detached from artistic communities and the urban contexts they pass through. A model that reduces culture to a product, audiences to targets, experience to consumption.

What is being emptied out is not only a certain way of producing culture, but a certain kind of social time: the everyday, continuous time made of relationships, practices, and shared presence. A time that does not generate profit peaks, but builds bonds. And it is precisely this time that is now being systematically eroded.

Taking a position has a cost. Organising is the answer

In this scenario, political conflicts within cultural spaces also produce material effects. What happened at TPO with the cancellation of the Earth concert was not an externally imposed act of repression, but the emergence of a political fracture. The band chose not to perform in the presence of the Palestinian flag on stage; for TPO, that flag is not a negotiable element, because it is part of its history and political positioning. The decision to cancel the concert carried economic and relational costs. Not because of censorship, but because taking a position today always comes at a price.

And this is where the difference between spaces and containers becomes clear. The response was not silence or retreat. In less than twenty-four hours, the crowdfunding campaign launched to support the space raised nearly €3,000. Not an act of charity, but a collective assumption of responsibility. Proof that these places exist because communities exist that inhabit them, sustain them, and defend them.

It is no coincidence that TPO hosted the national assembly “O Re o Libertà” on 24 and 25 January. Over two thousand people present and more than three thousand connected online, with 160 contributions in two days. Numbers that speak of a widespread need for dialogue and self-organisation, and that point to a possible political response to this scenario: convergence, presence, grassroots construction.

Because this is what we are really talking about: not only evictions, licences, or concerts, but the right to exist of entire segments of social life.

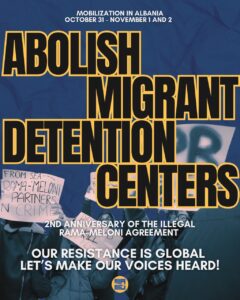

On 28 March in Rome, with the national mobilisation Together, held simultaneously with London against kings, their wars, and their systems of control, this demand attempts to become collective practice.

Not as symbolic testimony.

But as a political choice of alignment that is now more necessary than ever.