While we are writing this text, the class struggle in Serbia (pass us the term) is still raging. Governmental repression has continued even after the resignation of the prime minister, but the mobilizations did not slow down. The images of black and gray smoke bombs lit inside the parliament have also circulated around the world.

We were there in late January, exactly when Vucevic resigned. We decided to publish some considerations from that trip because we think they can be useful to give us some perspective on what is happening there and also to stimulate our mobilizations inside the Italian University.

We decided to go because we were attracted by online stories about what was happening. We wanted to engage especially with university students and researchers who were fueling the mobilization. As we talked to them, the enthusiasm, or even commotion, with which they greeted us is the best souvenir for those like us who seek to transform reality. However, it is important to note that, when talking about the ongoing movement, all our interlocutors were careful to expose themselves and measured the words they used well. As a disclaimer, we must admit that our view is certainly partial.

INTRODUCTION – A BIT OF HISTORY

After the civil war in Yugoslavia (1991-’95), which was particularly bloody, Serbia has been led by the secretary of the Communist Party, Slobodan Milosevic, who, until the beginning of the new millennium, fostered a particularly nationalist policy toward the other peoples of Yugoslavia.

In 2000 Milosevic’s regime fell and Serbia began to advance, albeit slowly and with contradictions, toward democracy. At first the transitional government seemed to be submerged by corruption and dysfunction. At the same time, in the first decade of the new millennium, the issue of Kosovo intensified: in 2008 Kosovo proclaimed itself an independent state with the recognition of the European Union. This is the reason for Serbian resentment toward the union, an unsolved issue resulting in an obstacle for Serbia in joining Europe. Consequently, in 2012 the Progressive Party began to gain public favour, emerging as the bearer of democracy, willing to end the corruption processes carried out by the previous ruling class. Aleksandar Vucic started to become a relevant figure within the party.

He began his political career in the government of the country very young: by the end of the 1990s he was secretary of the Radical Party (SRS) which in ’98 became part of the governing coalition together with the Socialist Party led, as mentioned earlier, by Milosevic. What is extremely interesting is that, according to one of our trusted Serbian informants, Vucic was not only minister of information in the coalition government, thus influencing and determining an extreme repression towards the Serbian anti-government media – a policy that largely conditioned the entire functionality of the media in the early 2000s (and we will later see that the complete repression of independent media is a widely used tool in Vucic’s current government). He also, and most notably, shifted from the radical right-wing nationalist party to the progressive party, once the previous governing coalition fell. In this party, Vucic would start to acquire political prominence, beginning his rise to the role of president of the nation.

In 2012, he was secretary of the Progressive Party and was first elected defense minister and deputy prime minister. Subsequently, in the 2014 elections he became prime minister and began the process of joining the European Union.

As his government consolidated, the progressive spirit began to give way to significantly authoritarian and increasingly corrupt power grabs, creating a hierarchy constructed ad hoc to consolidate a regime that followed the lines of authoritarianism, composed of personalities close to and loyal to the figure of Vucic and his associates. This produced a system based on the dependency of the various governmental figures, so dense that the entire system would be jeopardized should one piece of this pyramid fall. But as various people have told us, there was also some sort of “fear of chaos”, in the case of an actual fall of this system, within the whole government.

On top of this, an increased suppression of public dissent took place, and, at times, it became particularly violent.

In 2016, Vucic became president, and even the government opposition began to turn vocal in its accusations, denouncing him for restricting the media’s freedom of independent expression, as well as the ability of people to dissent. Not surprisingly, television channels became non-independent government channels, directly manipulating and monopolizing information. A further and decisive rupture occurred during the pandemic. It was a time of false promises, offered by the government to secure more votes, and by subsequent large protests suppressed with particular violence. Since that time, more or less throughout all Serbia, the repressive and corrupt nature of the government has come to light.

DIRECT DEMOCRACY

In addition to the pre-existing conditions, the Novi Sad tragedy, and the government’s attempt to hire hooded thugs to beat up the protesters, what made such a widespread mobilization possible was the broad participation in faculty blockades and their capillary organization.

The students, fed up with the silence of all political parties, not just the government, soon realized that waking the country up would be very difficult, since in the meantime they had to keep up with classes and exams. Hence, the courageous and rational decision to block the entire university and turn it into a space for organizing the movement with the aim of achieving their demands. From November to the time of our trip, the number of occupied faculties has multiplied, to the point of reaching almost all of the country’s faculties, which are about eighty.

The occupied universities have thus become a kind of institution for the general mobilization. Everything has been decided inside of them: the demands, the initiatives to be put in place, the methods, etc.

Each occupied faculty expresses its sovereignty in plenary assemblies, which have been the most important decision-making body. To put their decisions into practice, various working groups are in place: these are assemblies of a more restricted nature and with very practical outcomes that deal with specific issues, such as the relationship with the media, security, logistics within the university (food, beds, etc.), leisure activities, and others. More general decisions about the future steps of the entire student movement are made in assemblies, which, according to some of the students we spoke to, are very long and complex. In this context, elected representatives from each plenary meet and discuss based on the decisions and proposals of each faculty.

It is safe to say that in Serbia, and especially in the universities, a very interesting experiment of direct democracy is taking place. Except for the inter-faculty ones, each type of assembly they told us about is totally open to the students of the faculty who wish to participate. There is no fixed core-group of participants, and decisions are made by majority vote, by a show of hands. Everyone is free to make proposals which, if voted on, become immediately effective.

To give some sense of how the students have made this radically democratic organization method their own, we can think of the time we visited the faculty of political sciences. To allow us in, it was necessary for someone to propose, in the assembly, to make an exception to rules, in favour of “the small group of curious Italians”, and for this motion to be approved through vote. These precautions and rules were put in place to prevent outsiders paid by the government from coming in to see how the occupied faculties are organized. Basically, without a badge you could not get in, and the badge from the University of Bologna, up to that point, did not count.

It was funny when, just as we were chatting outside Political Science waiting for the assembly verdict, we found out that their organization had been described by the government as evidence of Croatian infiltrations inside the student movement.

The entire issue revolves around a document that came out after the 2009 occupation of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences in Zagreb. “The Occupation Cookbook” describes how the faculty occupation at the time was organized with a plenary assembly as well as working groups. It is not clear how true this story is. Still, we would recommend reading this document.

Another really remarkable thing about the blockades, and one that is undoubtedly strengthening the mobilizations, is that the overwhelming majority of professors fully agrees with their classes being blocked. We even saw professors entering the Faculty of Philosophy during an assembly, and students greeting each other like brothers with professors outside the Faculty of Veterinary – which, by the way, was the logistical center of the roadblock on the highway overpass that led to the prime minister’s resignation.

BEYOND THE FOUR REQUIREMENTS

As we left, we knew that only an 8-hour drive away from us was a country where the vast majority of faculties had been completely blocked for more than two months already. A manifesto was circulating on the internet, written by those same students who were urging us to do the same, claiming that the world was on the verge of collapse and that representative democracy was failing, putting our future at risk. When we arrived, we realized that that manifesto represented only part of a much broader horizon of practices and ideas. We discovered that it had been written by the plenary of the Faculty of Dramatic Arts (the first to be occupied) and that, probably because of its radical approach, it had never been approved by the entirety of the movement. Many told us that that was the “artists’ manifesto”. Well, you still have to give them credit: they wrote a good manifesto.

During our stay in Belgrade, we came to the understanding that the movement is demanding that those people, who were paid by the president to violently suppress the protests, undergo a regular trial by the judiciary. The aim is to prevent such incidents from happening again.

It demands that the officials who signed the papers regarding Novi Sad declare and publish the truth.

It demands, beyond the events of the station, that the Serbian state begins to function according to its own constitution, that corrupt state apparatuses be tried by the judiciary, and that newspapers and television no longer be means of government propaganda but real independent news media.

To read more on the requests, see the two articles we have written in municipiozero:

By talking to people, we sensed that the general hope of the movement is, in short, to shake the country to the point of finally making state apparatuses function as they should in a democracy based on the European model. The claim has become “more democracy”. We know that this model has many flaws: think of how, in Italy, the relationship between politics, the judiciary and the media has changed profoundly in the last few years; think of all the cases where the police obstructs the judiciary truth about a deadly incident, of the bribes and agreements with businessmen and mafiosi, and the construction industry violations. Yet, from there, the view is different. A democracy like ours would certainly be a nice improvement over a system where one party stays in government for more than a decade and the president manages deals under the table with companies, the EU – we will try to expand on the relationship with the latter in another publication – and China.

The question we asked, however, was: “How can you move from widespread university blockades to a new state system, no longer based on informal power relations and corruption?” Obviously things are constantly evolving, but, talking to many of them, it seemed to us that this question was not among their priorities. Or we could say, at least, that the mobilization was very much focused on the four requests.

This politics based on requests rather than transformative proposals is, in all likelihood, precisely the result of the direct democracy put in place by a movement made up of students with different ambitions and opinions. Certainly it is what is allowing a massive and heterogeneous presence in the streets: the requests are clear and simple, everyone knows and understands them. Until the Serbian state publishes all the documents, everyone will remain in agitation. This is one point that appeared to us essential for the strength of the mobilizations.

What will happen next? No one could give us an answer to this question.

The crux of the matter is that people are not calling for new elections or for a change in the governing party: they are calling for systemic change, but they are afraid to make a political proposal that goes beyond compliance with the law and the constitution. The students we talked to were afraid that such a proposal might expose its potential leaders to easy attacks by government apparatuses and the media controlled by them, but they were especially afraid that a proposal – which could potentially be divisive – might bring the mobilizations to a stall and add to the institutional immobility, and to the deadlock of the movement as well. Considering the facts, these are doubts and questions that perhaps are already outdated, and it will be our interest to explore them further.

As we wrote at the beginning, simplifying, the class struggle in Serbia, which at this point we might call the struggle for democracy, seems to be continuing.

FOR A MOBILIZATION INSIDE THE UNIVERSITY

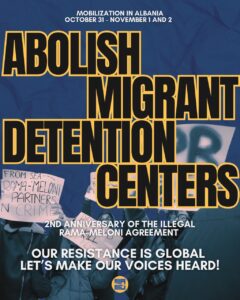

After the trip was over, we immediately started thinking about the positive insights we could bring back to Italy. In 2024, we witnessed the increasing desire for activation of young people in our country, we saw it with the encampments for Palestine, we saw it with the growing networks of university students, who no longer tolerate the prospect of a precarious future. We are continuing to see it with the increasing discontent with the government, its irrational laws, its agreements with the world oligarchy and its frivolous attempts to solve a real security problem by putting activists and migrants in jail through ad hoc laws.

Coming back from Serbia, we reflected on how, perhaps, our struggles lacked enough organizational capacity to create a real convergence and, especially, a narrative accessible to everyone, like the one created there.

We think that the struggle for a public university should be the space to experiment new practices and that, instead of just reacting, it should be able to make proposals. It should be a stepping stone, in dialogue with struggles all over Europe, to imagine a mobilization up to the challenges of the present.

Students in Serbia literally began making history. Keeping our differences in mind, we should do the same.

As someone would have said:

Students of the world, join the blockades!